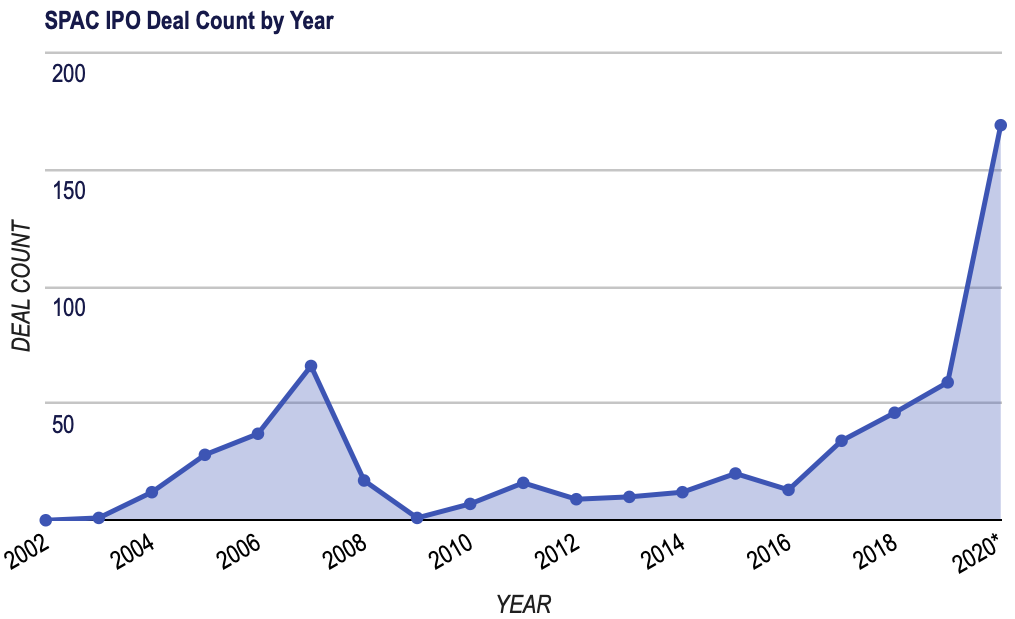

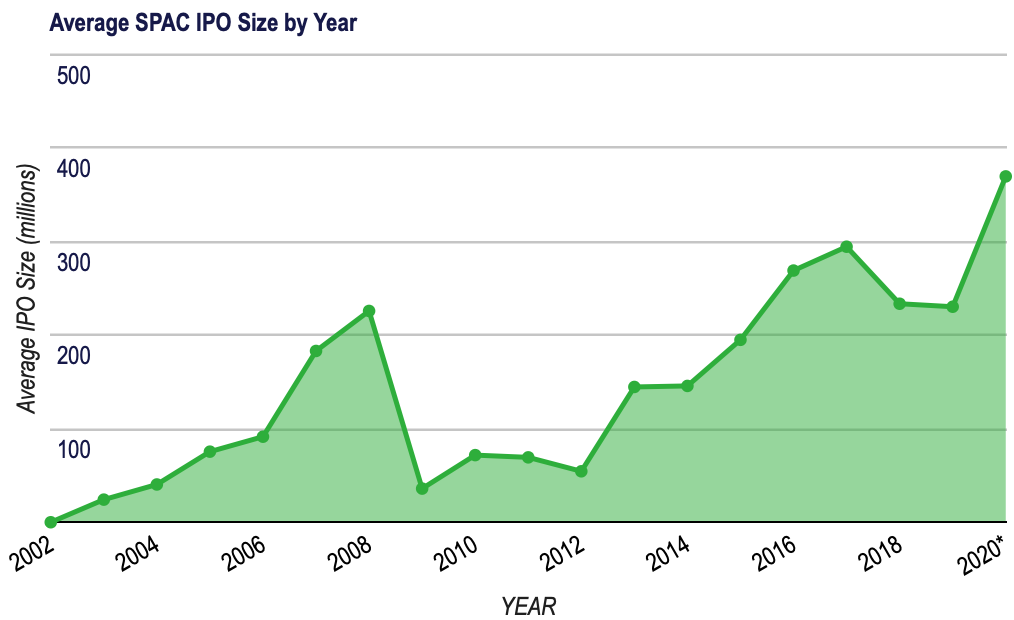

Faraday Future, the electric vehicle startup hyped as a rival to Tesla, has been eyeing a public listing through a deal with a special purpose acquisition company (SPACs). The startup’s CEO says that the company is working on a deal that will be announced: “hopefully quite soon.” Faraday’s action falls into the pool of 166 SPAC IPOs up to October 29, 2020. In fact, 2020 has been a record year for the formation of SPACs given that initial public offerings (IPOs) of SPACs have raised nearly $59.4 billion in gross proceeds, which is far higher than $13.6 billion in gross proceeds raised by SPACs in 2019 or the $10.8 billion in 2018.

SPACs originated from the development and emergence of “blank check companies” in the 1980s. Like blank check companies, SPACs are vehicles with no operating history, assets, revenue, or operations that are formed to raise capital in a public offering, will be used to acquire an existing company.

After a SPAC is established, its business model is simple: use the SPAC as a shell company to raise money from investors in an IPO, and then target and merge with a company seeking to go public. Unlike a reverse triangular merger, in which an acquiring company creates a subsidiary, merges its subsidiary into a target company, and then becomes the parent company of the target, here, the company itself is targeted by the SPAC vehicle, which will absorb it and take it public.

SPAC deals are appealing for companies that want to go public with less regulatory hurdles than a traditional flotation. For example, with a SPAC a company can announce the merger after the price and the size of the deal have been settled. In contrast, a company seeking to conduct a conventional IPO must file a detailed registration statement, respond to SEC inquiries concerning, and conform all communications to a complicated set of speech regulations (i.e., the “gun jumping rules”) before it can begin the process of pricing the IPO. Given these regulatory differences, SPAC deals are much faster and more certain than the traditional option. The Covid-19 pandemic and the resulting national shutdown have also complicated the issuers’ ability in an IPO to meet with investors for purposes of pricing a conventional IPO. SPACs offer a potential alternative.

The question now is whether a SPAC will become a mainstream option for companies that seek a public listing. While the rapid growth in these vehicles in recent years points in that direction, the potential disadvantages outweigh this conclusion.

First, the top advantage of SPACs for a company seeking to go public is its speed and certainty. However, a merger between a SPAC and a target company could fail if the SPAC’s shareholders vote against the merger. In the past, around 10% of mergers by SPACs have failed for this reason. For instance, in April 2020, TGI Fridays, a highly-recognized American brand, terminated its merger with Allegro Merger, a SPAC. According to the deal’s form 8-K file with the SEC, the reason was “extraordinary market conditions and the failure to meet necessary closing condit ions” during the COVID-19 pandemic. Another example of a SPAC that failed after the merger related to Akazoo S.A. Akazoo S.A. was the product of a September 2019 merger between a SPAC called Modern Media Acquisition Corp. (MMAC) and Akazoo. Ltd., an AI music streaming company. The merger was completed prior to the September 17, 2019 deadline for MMAC, otherwise it would have had to return all of the funds from its trust account and wind up the SPAC. However, after the merger, news came out that Akazoo Ltd. was a massive accounting fraud, making their proclaimed 5.5 million subscribers a moot point. On June 1, 2020, Nasdaq Stock Market announced that it would delist the ordinary shares and warrants of Akazoo S.A. As such, the sponsors suffered significant losses and filed a lawsuit on misrepresentation. Rencently, on September 30, 2020, the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) also filed a lawsuit against Akazoo S.A. and its original management team (not including MMAC and its directors and officers), alleging that it “grossly misrepresented the nature and success of its music streaming business.” To sum up, the uncertainty of a successful merger may come from either a SPAC or a target. Nevertheless, when the parties cannot benefit from the certainty of a successful listing, both of them will leave the market.

Second, the target company’s founders are more vulnerable to losing control of the company during a SPAC transaction than in a conventional IPO. In an IPO, the new shareholders of the company are typically individual investors and long-term institutional investors. Thus, the incumbent management typically retains a degree of autonomy. However, in a SPAC transaction, the SPAC sponsor typically expects to obtain representation on the surviving company’s board of directors, allowing the sponsor to participate in the company’s decision-making process. Therefore, a founder who intends to preserve his decision-making power may be unwilling to go public through a SPAC.

Third, a SPAC transaction causes more dilution for the company than an IPO. As we discussed above, the SPAC investors invest at greater risk than in a traditional offering. Thus, in addition to a formal discount, most SPACs compensate sponsors by giving them 20% of the entire share capital of a SPAC upon its IPO, which translates into an often-substantial ownership claim in the target following the SPAC merger. Additionally, during a SPAC’s initial public offering, investors in a SPAC are given warrants in addition to common shares, which can convert into shares of the target’s common stock following the merger, further diluting the existing shareholders of the target company.

In conclusion, SPACs are more likely a flash in the pan. This new option for companies has a long way to go before it replaces the traditional IPO, and with growth in the space, regulation will likely follow.